Spray your web application with Gatling !

Hi everyone, there’s a long time ! Today, we’ll see the performance testing framework gatling which I could use during my intership of end of studies and I’ll show you how easy to use it is!

_Logo.png)

Introduction

Why Gatling ?

- DSL to write scenarios

- High performance

- HTML Report

- Community reactive

- Graphite integration

- And for lazy people, there’s a tool to create scenarios from your utilization of the web application using your web browser

Case study

To optimize your performances tests, you’ll need to detect each use case of your webapp. We’ll call each use case "Personas". For my blog, I found two:

- Readers who followed a link

- People who came randomly (google, twitter, etc…)

In the first case, the user will pass a long time in the article (reading it I suppose or I prefer not to know in fact), only that. And for the second case, we’ll have a random browse of the blog.

I will detect processes during my campaign. We’ll group them by purpose. Here I’ll have only one group "Browse" because they are the only functionnality I’ll test. So inside the Scenario.scala file:

|

|

Personas Representation

Now we have all the functions to simulate our users, let’s create our personas.

In the Scenario.scala

|

|

Here, we don’t have any complex functionality so our personas definition is quite easy but it can get quite tricky.

Developping scenarios

Simulation

Now we have our personas, we need to create the simulation, for that, you’ll need to:

- Fix the goals of your webapp (Reponse time, availability, etc...)

- Define the quantity of user you’ll send

In my case, I want my website to respond in less than 2 seconds for 100 users at the same time

Inside the Scenario.scala file

|

|

To execute our simulation, we need to use the gatling maven plugin. So inside our pom.xml, we’ll add this lines :

|

|

Now, we can execute our simulation with this maven command:

mvn test

Sessions

Sessions will allow you to save information during your simulation. These sessions are basically Maps of String, Any. You’ll be able to inject in your sessions datas thanks to feeders or retrieving them with the Expression language of Gatling or, if you need to, using the Session API.

Feeders

Feeders are built to inject datas from an other source. You can inject data with this specific feeders :

- CSV feeders

- JSON feeders

- JDBC feeders

- Sitemaps feeders

For example, in my case, I will use the sitemap feeder to browse all posts in the blog and do the same test to check theirs no lack of performance for one specific post. Oh thats, a good idea, I need to make that.

The Expression Language

With the Expression Language (EL) of gatling, you’ll be able to access easily to datas in the session. You can access to your data specifying in a string ${mydatatInTheSession}. In the case, you add something more sophisticated as JSON, Map, you can specify the jsonPath of the element you want to reach. Example: I save in my session these variables:

|

|

I want to access to the second link with the EL:

${record2.loc}

Nice, isn’t it ?

PS: I forgot to say that the EL is used only inside strings. So for the previous example, i’ll declare it like that:

var url: String = "${record2.loc}"

Session API

With this API, you’ll be able to manipulate the session directly with getters and setters. Example:

|

|

WARNING: Be careful with the getters, if you don’t specify the type you’re expecting, the session will return a SessionAttribute instead of the type expected, so NEVER FORGET THE .as[type].

Goals

Now, we have requests, but that will not tell us if the webapp respects our expectations. To check that, you’ll have to add checks and assertions.

Firstly, you can specify the HTTP code you’re expecting after each request. I’ll used this kind of checks in the personas creation. Let’s see it again:

|

|

We check if the HTTP code in the response is 200. If not, the call is failed.

And we have the assertions which will allow us to define if a call is acceptable or not if the performance goals are respected. This assertions are defined at the same time as the setUp function (where we define how many user we are injecting in the simulation).

If we change the Scenario.scala file, it will be:

|

|

Reports

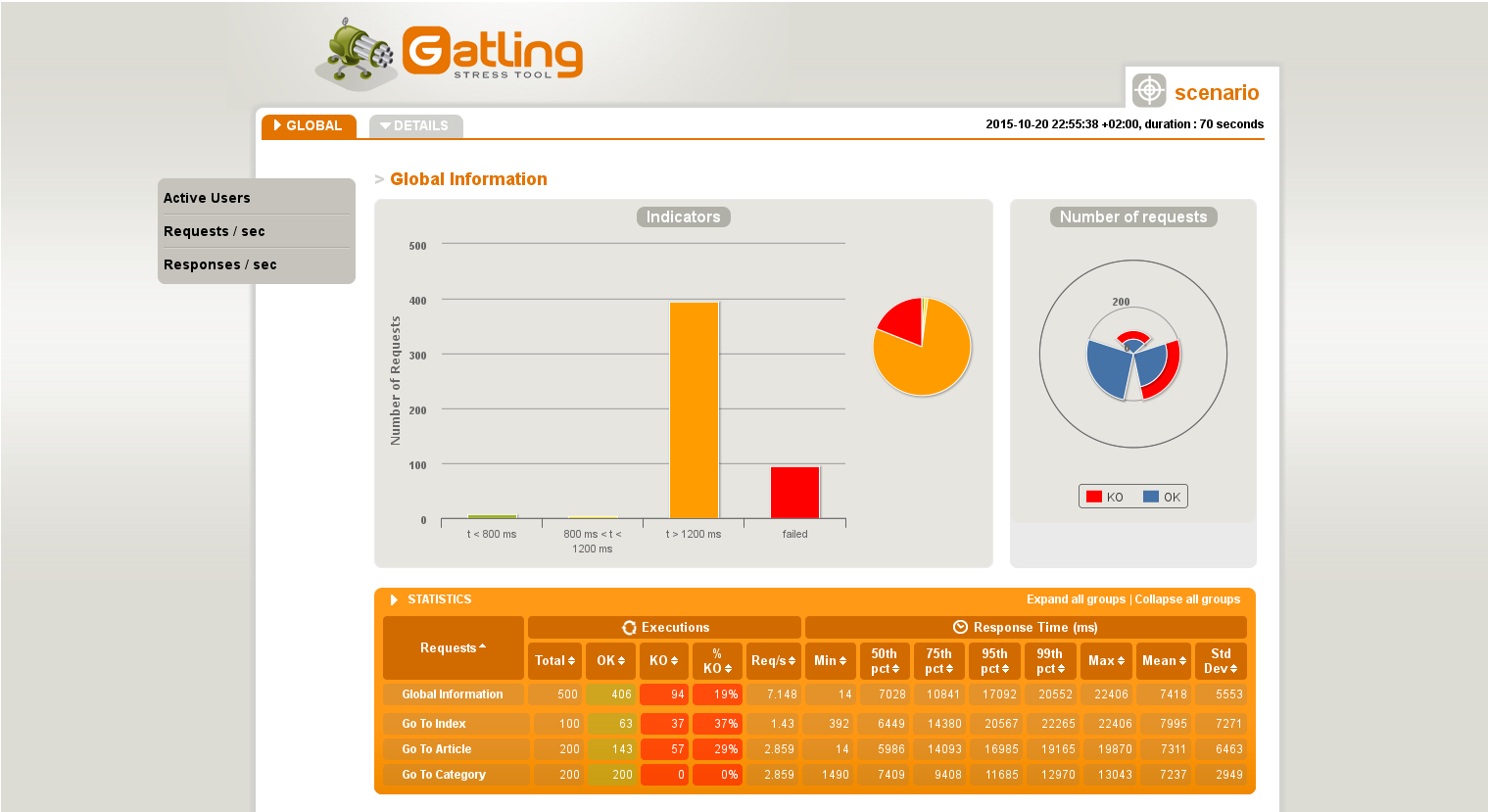

After each simulation, Gatling will create html files containing all the results of your simulation inside your target folder (if you’re using the maven plugin). Inside each report, you’ll have two sections, one for the globality of the simulation and one detailed for each kind of requests.

Here we can see that most of the requests failed :'( :'(

Monitoring

What is pretty cool with gatling is it’s easy to integrate it to a monitoring tool such as graphite. You’ll need to add few lines in your gatling configuration and all your datas will be published inside of it.

TIME TO CODE OR TO CONFIGURE GATLING:

- Add a gatling.conf file at the root of your project.

- Add these lines inside the file

Bam, just that and everything is sent to graphite! You can even specify that you only want to send all the global datas, choose which protocol to use, change where the datas will be published in graphite, etc…

Tricks

Jenkins integration

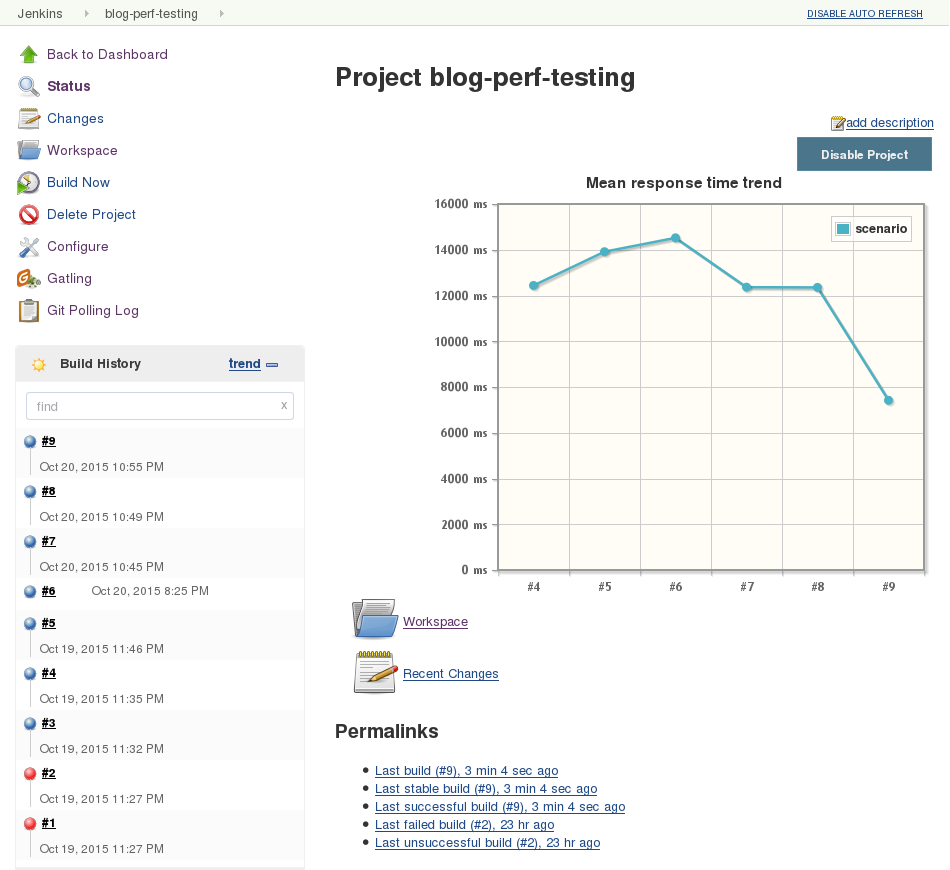

You can run your gatling simulations with integrations servers

such as Jenkins. I use it to launch every day the tests so I have

tendancies about the performance of the blog. You can also add the

Jenkins’s gatling plugin and you’ll have a display of the result of

your simulation execution.

Debug Time

To debug, it’s quite simple. You need to use the exec and the session variable to debug what you want (in fact it’s not that simple). Example:

|

|

Conclusion

I think we see quite a lot of what offer this framework. We can still talk about request timing, controlling curves of users, but I invite you to read the doc for more detail. If you have any questions, don’t hesitate one second to post a comment, I’ll be glad to respond to it. (unless it’s for #!/bin/bash juanwolf (looooooool).

I hope to see you coding few scenarios, but I need to go, I have Rollerblades to try. Sur ce, codez bien.